Who’s Out There? [Coal Asia Vol. 39]

![]()

Who’s out there?

By Ian Wollff

The author is an expatriate principal geologist of about 28 years experience in the Indonesian exploration & mining industry, and is employed by an international consultant company.

From a standing start

Following the disruption of the Second World War, and Indonesia’s war of independence, the Indonesian universities only had a small number of lecturers and students. The outlook of students entering these early universities was to focus on faculties of high community moral outlook, with medical doctors and teachers carrying a high social status. The science of geology and mining was somewhat of an oddity, with getting a job in the government or a state run company being the envisaged outcome. The first doctorate in Geology was issued from the Dutch origin Technische Hogeschool te Bandung (TH) in 1958 with the change to Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB) on the 2 March 1959, being the first Indonesian university to provide a science degree for the graduation of geologists and mining engineers.

The implementation of the Contract of Work (COW) system for the participation of private enterprise in the development of the Indonesian exploration and mining industry for minerals and coal was accompanied by a rapid demand for manpower with specialist skills. To meet the needs of the COW performance clauses, the private company’s imported geologists, surveyors, miners, drillers and other experts to kick start their exploration business. In doing so, the COW system provided a huge stimulus to universities to develop their science faculties to meet the growing number of student’s interest to enter the geology and mining sector. The motivation of these early graduates was a mix of national pride in the scientific discovery of their own country, further learning through the counterpart system, and opportunism in a developing industry and the lure of good wages as set by the international expatriates.

Upon entering the work force some graduates found the remote and rough life style was a cultural shock and sought simpler office jobs in the government or left the exploration sector. Fortunately other Indonesian graduates persisted, and so lead the first wave of eager explorers to develop regional geological maps by the government and others to start building skill sets in the private sector under the guidance of some of the world’s leading explorers for gold, copper, bauxite, coal, nickel etc. The industry has grown, and many of these early geologists and miners are now Indonesia’s industry leaders.

A recent presentation prepared by a special committee to report to the Indonesian President [Penyipan Data Sarjana Teknik Unitk MP3EI prepared by Persatuan Insinyur Indonesia] reflected a great difficulty in determining the number of engineers (including geology and mining) in Indonesia. However they did estimate that in 2011 about 1.4% of engineers were engaged in the mining sector, and concluded more engineers and more education budget was needed. They also noted that in 2009, mining contributed about 10.53% of Indonesia’s GDP with about 1.09% of the work force. More recent industry reviews indicate the mining sector contributes significantly more to Indonesia’s GDP, though the data on graduates in the geology and mining are not recorded.

Getting Started

The nature of recruitment of fresh geology and mining graduates is always changing. In past years top explorers would meet key university professors to identify the best students. Then the companies made a personal approach to the targeted students to offer vocation work and thereby developed a company brand image as being a preferred company to work with. The top graduates moved seamlessly into a desirable work environment. Other students would seek work from a variety of exploration companies, where the companies Human Resources (HR) department would sift through mountains of applicants that looked so similar. In the early years nepotism was not well developed, possibly as this was a new science and required individual talent and commitment to an often difficult life style. However some trends did emerge where one company may contain most of its graduates from one university, or have a strong ethnic preference, and sometimes there was preferred for a mix of religions, such that work would be led disrupted by the main religious holidays.

Moving Up

The early years of the COW system saw semi skilled Indonesians in the mining sector undergo well developed in-house training programs to learn to drive large trucks, maintain mining fleets and such. However there was no corresponding concerted rush to train geologists in a structural manner. They started with repetitive basic jobs that were designed to fit with their limited education. Many geologist throughout the world follow this “learning from your elders” approach where the practical skills of core logging, stream sediment sampling etc, are an informal form of apprenticeship. The geologist develops his “craft” in a series of steps from junior geologist, geologist to senior geologist, project geologist etc. Government and industry acknowledge this career path development, as the new Indonesian regulations stipulate reports submitted the mines department must be completed by geologists with at least 3 years experience. Similarly reports prepared in compliance with the JORC code are generally by geologists with at least 5 years relevant experience.

The university learning process sometimes produces graduates that have a strong team working outlook, where they share the responsibility to complete a task. This can readily be transposed into a big company where the work tasks are divided up amongst a team. However this outlook does not always help the company or the new geologists or engineers. One tendency is towards smaller companies and fast moving exploration projects that require geologists to take initiative, and apply individual performance KPI’s.

There use to be a reasonable number of targeted training courses for company geologist and mining engineers in areas to advance exploration techniques, or to train people on new geophysical or geotechnical techniques. Today some of those breakthrough techniques for minerals and coal exploration are incorporated into university courses. Some of today’s training courses serve a dual purpose, such as computer modeling for a new branded software product, or assay techniques by a laboratory seeking to advertise its new equipment. Fortunately the Indonesian Petroleum Association continues to provide serious extra training courses in a wide variety of geological fields.

The nature of the Indonesian exploration industry has also progressed. Early exploration company philosophy was one of commitment to a patient discovery process, reflecting a long term commitment to the industry. However many companies are now being lead by an impatient management seeking quick results with limited funds or limited commitment. This focus on quick results tends to skip over the aspect of further formal training programs, or uses seminars as a way of rewarding staff, rather than earnestly seeking to better their skill sets.

The nature of learning has also changed, trending towards a less structured learning environment through the internet, short seminars and conferences. However the most effective learning process is also the oldest approach, where wiser geologists and miners pass on their experience to the younger engineers. This can also be the most cost effective arrangement for companies, wherein the learning curve is shortened, and the old adage of; “Don’t learn by your mistakes, learn from the mistakes of others!” applies.

The Top Job

Indonesian companies senior officers and directors often involve some form of family or old-school-tie style of nepotism, but other forms of nepotism may be encountered. In some foreign owned firms, leadership remains with the foreign nationals as a reflection of their trust and philosophy. Some national companies are lead by a series of financial officers with emphases on managing the finances as generated by the mine, rather than a geologist or miner with emphases on managing the mine that makes the money.

Frustration over lack of advancement opportunities to the top levels of management can lead some geologists and miners to start their own companies. Such an outlook is similar for all countries and a reflection of a developing mining industry, not just Indonesia.

Who’s out there

Finding statistics on the number of Indonesian higher education, lecturers, students and active geologists and miners is difficult. The author sent letters of enquiries to 30 universities, 6 Institutes of Technology, 7 Sekolar Tinggi (trade schools), 4 Academes and 7 Polytechnics seeking historic and present numbers of students, and lecturers in the fields of geology, mining, mineral processing, geochemistry, geotechnical engineering etc, however none responded. Of these about 27 tertiary institutions provide geology graduates, while the remainder holds some geological lectures in support of mining graduates etc. Discussions with a retired university rector confirmed that such higher education institutes in Indonesia are very poor in participating in such enquiries, even when sought by government departments etc.

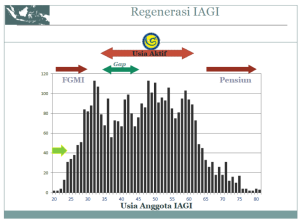

It would seem most of the geological and mining associations do not keep good records of membership related to profession. However the Indonesian Geological Association (Ikatan Ahli Geologi Indonesia_IAGI) has about 4,000 members engaged in the fields of education (410), Government (467), Oil & Gas (966), Mining (337), Other (371), unknown (1319) and provided a graph of members age distribution.

Not all Indonesian geologists are registered with IAGI, with some preferring other associations, particularly the mining orientated association of PERHAPI. Some geologists belong to several associations, including HAGI (geophysics), IATMI (Oil & Gas), API (geothermal), Geohydrology, MAPIN (mapping & geodesy), ISI (surveyor) plus IPA (Oil & gas with 1,500members including non geology & mining engineers).

Other avenues to seek numbers of geologist and mining students were sought through the web sites of the ministry of statistics, ministry of education, ministry of mining & energy were fruitless.

Indonesian outlook on the Quality of Indonesian graduates.

Personal discussions with a number of Indonesian industry leaders in the fields of geology, mining and education plus a number of experienced geologists all confer that there are only about 5 universities producing good quality geologists. This is principally a reflection of the standard of students entering, the experience of the lecturers, and lastly the facilities.

Outlook of international institutions on Indonesian graduates. [Note, the reader is recommended to view the source documents from the web].

The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) is a business and research unit of the McKinsey & Company that issued the report titled; “The Archipelago Economy; Unleashing Indonesia’s Potential” (September 2012).The report makes a number of points to emphasize that Indonesia should take action to boost productivity in a number of areas, including the resource sector, and to remove constraints on growth. One such constraint is the estimation that significantly more tertiary educated people shall be needed in the future and that standards of teaching need to be improved. One indicator of the quality of education was a survey by the World Bank that found 41% of employers reported gaps in their graduates ability to think creatively and critically. One of the conclusions is that the uneven growth across the archipelago is rising concerns about inequality.

The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) report (“Growing Pains, Lasting Advantages”, of May 2013) indicates Indonesia now has more than 1,000 universities and colleges, though top executives indicate only a few such universities and colleges provide top quality graduates. There are about 30,000 engineers graduates per year, but Indonesia needs about 50,000. The BCG indicates that leading industries tend to improve their management team through poaching employees from other companies, rather than invest in university scholarships, provide in house training or other long term strategies to build a successful team. In sectors such as banking or sales this poaching may eventually lead to companies losing their competitiveness. However this author feels this outlook on poaching is beneficial to the industry for the geology and mining sector as it has long been recognized that professionals moving from one company to another and from one geological setting to another ultimately provides the professional with a broader view of the science and the industry that drives it.

The Asia-Europe Foundation (ASEF) published the 3rd ASEM Rectors Conference titled “Universities, Business and You; For a Sustainable Future” (September 2012). Several rectors from Indonesian universities contributed to the outcome of this conference. This conference focus was related to the concept that Universities are motors for economic growth and that close co-operation between education and industry is a core element of ensuring the employability of the young generation entering the workforce. Some conclusions include; “The challenges that universities need to tackle together with all stakeholders are: financing, selection and admission. Access can only be really effective if we fully engage employers as crucial stakeholders”.[Prof.Dr.Akhmaloka at ITB].” And “Listening to and engaging with community and industrial partners. [Prof. Iwan Dwiprahasto at University of Gadjah Mada]”.

The 4th Asia-Europe Meeting of Ministers of Education (ASEMME4) titled Strategizing ASEM Education Collaboration (May 2013). The ministers agreed on a number of concrete activities and measures to be carried out, including;

- Acknowledged that quality assurance, qualifications frameworks and recognition are essential for building trust and facilitating the recognition of degrees and diplomas.

- Aware of the different regional credit systems for academic recognition, they emphasized the need to make these systems more transparent in order to facilitate recognition of study achievements abroad and to stimulate cross-border mobility.

- Encourage all stakeholders involved in education and business to engage in further efforts to enhance the employability of higher education students, and so encourage the business sector to define the competences they need.

Conclusion

1. Obtaining reliable data on Indonesia’s geology and mining students and professionals is difficult, and thus government ministries may not be able to properly determine Indonesia’s growth characteristics in the increasingly important areas of oil and mineral development, natural disaster mitigation etc.

2. There appears to be no suitable mechanisms to properly gauge the quality of Indonesia’s graduates, and thus the opportunity to work towards the improvement in human resources is hampered.

3. Senior professionals in the higher education and mining sectors agree that more effort in determining the syllabus should reflect the industries needs. It follows that science should be emphasized in all levels of school, contrary to the present parliamentary plan to abolish science as a specific subject in junior school.

4. Indonesia’s next generation of geologists will have to be even smarter to discover future new oil and mineral wealth. The geology and mining industry needs to be proactive in attracting Indonesia’s best minds into the geology and mining sector. This may be done through providing better scholarships, grants etc, and to emphasize that responsible exploration and mining brings significant benefit to the Indonesian people. Exploration and mining is a 21st Century high moral value and socially responsible profession.